On Internet Art

In an essay published this week by urs truly in Spike Art Magazine, “What’s After Post-Internet Art?”, I try to pin down new ideas and aesthetics in internet- and technology-imbued art. I call it “technoromanticism”: a turn toward material beauty, gothicism, subjectivity, and the sublime. This is a rider for that essay, so I suggest reading it first and returning here where I get into some implications and ideas surrounding the piece that didn’t make it in.

Post-post-internet

My essay suggests, via the voice of other critics, that post-internet art is done, but that’s not really true, despite many writers opining its formal end. See Orit Gat’s declaration in Frieze last November for just the latest in a chain of eulogies. It’s simply become a meaningless term: all art is post-internet art now. There is no art made today that isn’t influenced by the background radiation of the internet. Many of the big names in net art and post-internet art have blended their work into somewhat standard contemporary art practices. Cory Arcangel is a post-conceptual minimalist now; Petra Cortright a digital expressionist.

Art made on and about “the internet”, taken broadly as networked society, digital systems and its physical and virtual infrastructure, naturally lives on. Early post-internet art approached the digital like early conceptual artists did the dematerialized object—aping on the commodity form and defining the outlines of a new medium, the social internet. That job seems to be done, it’s true. But the techno-capitalist wellspring is ever-giving for conceptual artists to shake their fists at. Now, post-conceptual art is politically driven and research-based, and often responds to predominant political-technological forces. Contemporary theorists call its present forms, variously, surveillance capitalism (Shoshana Zuboff), platform capitalism (Nick Srnicek), technofeudalism (Yanis Varoufakis), etc.

Artists of all stages investigate the infrastructure of digital economics, media platforms, big data operations, and online conspiracies. See Simon Denny’s Divider series (2023), made up of print-paintings and office materials acquired from the Twitter office liquidation after its purchase by Elon Musk. His exhibition, Read Write Own, is up at Dunkunsthalle in NYC until March 31st. Also see Poetics of Encryption in Berlin at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art, a “[survey of] an imaginative landscape marked by Black Sites, Black Boxes, and Black Holes—terms that indicate how technical systems capture users; how they work in stealth; and how they distort cultural space-time”.

Internet core

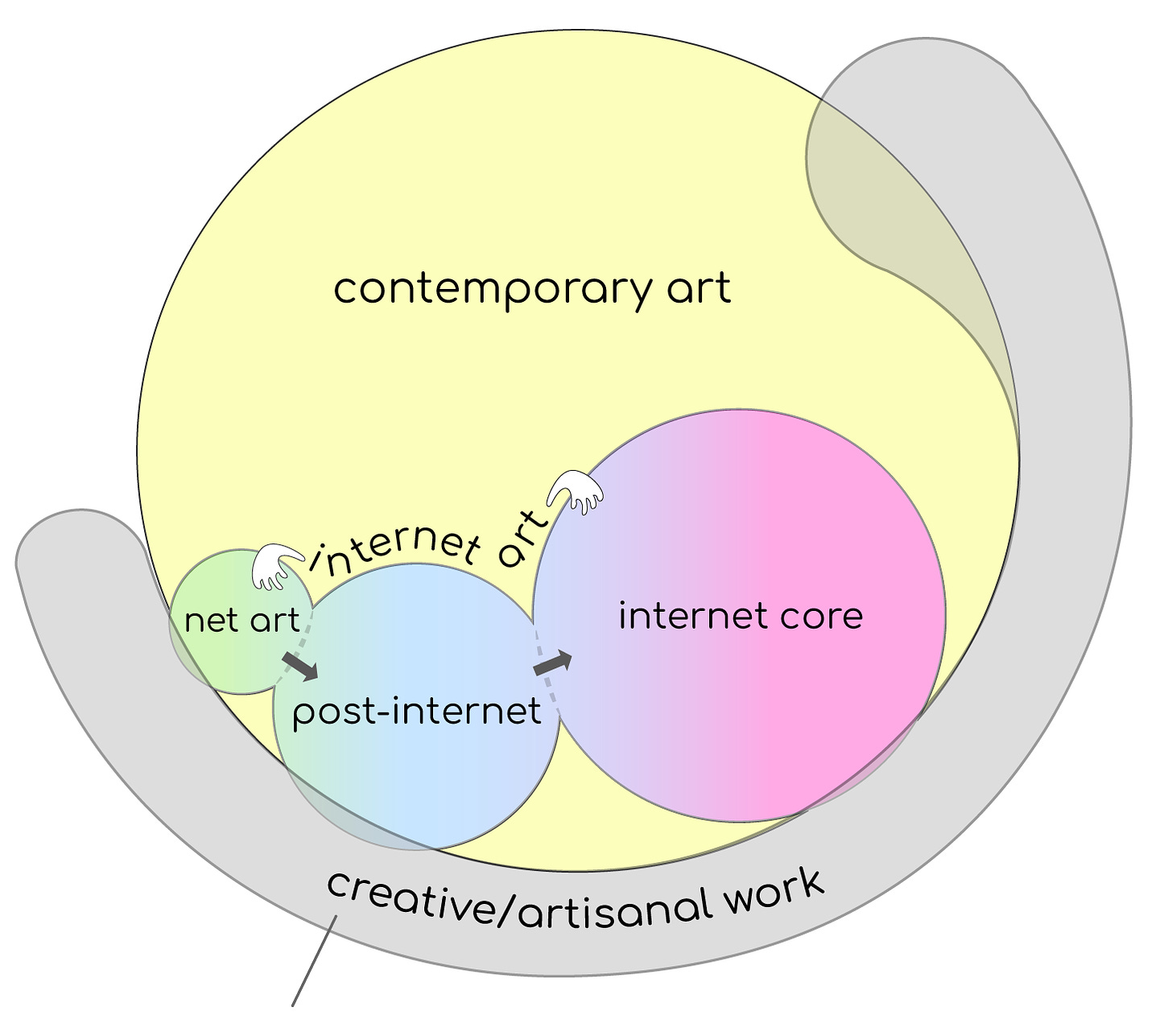

Twee Whistler offers an adjacent take on emerging art after post-internet in “Internet Core”, published in Do Not Research last summer. In her essay, Whistler lays out various movements of internet art within the bubble of contemporary art, with internet core as post-internet’s successor, offering this illustration:

For Whistler, internet core “has mainly works conceived in a social media format”, which “[see] the resurgence of deep-fried memes online”, and which “aren't fully digestible and patinated, but a bit dissonant, unsatisfying, incomprehensible, and chaotic.” Whistler, it seems, is specifically referring to the meme-influenced digital subculture that spreads across anonymous accounts on Instagram whose art leaks into film and the plastic arts, and occasionally bubbling up into devirtualized art spaces, galleries, and DIY shows. Whistler has identified something, but something I believe is far more obscure and “artisanal” than what her diagram suggests.

She references the internet core–coded Do Not Research group show held in 2022. In the show’s documentation I can see at least a few pieces that are essentially printed-out memes. I see a series of “network spirituality” memes on the wall, and another wall piece comprising an emergency kit, a pink cosplay wig, and a monster energy drink. Funny. This kind of work is appropriates niche meme culture, which lately relishes in Dadaist, schizoaffective, and conspiratorial ramblings. Overly-online artists are enchanted with online subculture which problematically fetishizes white underage anime girls and gets lost in its own self-referential esotericism. If internet core takes up the internet as medium with memes as its language, then its art is bound to the same fate as every meme: instant death and future cringe fodder. It might be radical online, but in a gallery setting—where it’s forced to take itself seriously—I think it looks a bit goofy, and like the mass media it resembles, might not age very well.

Technoromanticism

The angle I take in my essay is that a distinct set of emerging fine artists are reacting against the overburdened hyper-rationalization and quantification of life as we know it. Conceptual art is just one response—one that’s more associated with an older generation coming out of the post-internet period—and which has been repeatedly criticized for its insidious ambivalence and false radical posturing. The technoromantic artist, however, does not make any such claims. They are distinctly materialistic. They turn to the past, revive renaissance and medieval motifs, and reimagine contemporary nightmares as Gothic horrors and classical myths. The mysticism of the old world becomes a compelling source of inspiration, as do traditional art methods and emerging technologies alike, whether it’s painting or 3D printing (or both at the same time).

I considered alternative names: “internet romanticism”, “devirtualism”, and “post-post-internet”. The techno- prefix means “connected with technology” and derives from the Greek tekhnē (art, craft). We can see this prefix in “technofeudalism” and the “technocene”, the former mentioned in my essay and the latter in Nadim Samman’s Poetics of Encryption (both an exhibition and a 2023 book). The term was posed as far back as 2017 in an article in Techné from 2017. In the abstract, Agostino Cera writes:

[Technology] emerges as the oikos of contemporary humanity. Technology becomes the current form of the world—and so gives birth to a Technocene—insofar as it introduces in any human context its ratio operandi and so assimilates man to an animal condition, i.e., an environmental one. Technocene corresponds on the one side to the emergence of technology as (Neo)environment and on the other to the feralization of man. The spirit of Technocene turns out to be the complete redefinition of the anthropic perimeter.

The technocene suggests a pervasive ambience of the internet as an environmental factor which acts upon all of its inhabitants. This is my stance on the internet as a global force, which spawns all manner of intellectual and artistic responses—including technoromanticism, internet core, and S-tier contemporary art alike.